Victorian records management stuck in the 70s

In the year Victoria’s Public Records Act 1973 was enacted, flared pants, flower-power shirts with massive wing collars and monster sideburns were the order of the day. However the average public sector worker’s desktop would have housed only a few unsexy peripherals perhaps not much more than an in-tray, a pen and notepad and an ashtray. A major review of the Management of Public Sector Records in the state completed by the Victorian Auditor-General has found that record-keeping practice has not kept pace with the vast change in the information management landscape since those times.

“Victoria’s information management environment is highly fragmented and disconnected - with multiple sets of policies and standards that can sometimes contradict each other,” it notes.

“These weaknesses - particularly the absence of system-wide compliance monitoring and reporting and outdated legislation - heighten the risk of key government records being lost, inaccessible, inappropriately accessed, unlawfully altered or destroyed.”

Some of the seeds of the IT revolution were sown in the same year as the outdated 44-year old Act. In 1973 Robert Metcalfe created Ethernet networking and Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn developed gateway routing computers to negotiate between the various national networks, the first internetworking.

“Victoria’s information management landscape has changed significantly since the Act was first established. Today’s business environment is now vastly different,” the report concludes.

“The volume of records created and held by agencies and third-party providers has also increased significantly. At the same time, new business practices and advances in technology have increased the risks relating to information integrity, accessibility, security and preservation.”

In addition to its review of the Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), the Auditor-General’s report also examined the records management practices of two individual state agencies in detail: the Department of Education and Training (DET) with more than 58,000 staff and the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) with a staff of 10,000+.

Neither agency was found to be fully compliant with legislative requirements.

“Consequently, neither agency sufficiently understands the records it owns and holds, and cannot be assured that their records are being effectively managed and maintained. Encouragingly, both agencies acknowledge these issues, and have started to address them.

“People who create and manage records - which, in today’s digital age is all public sector staff, as well as its contractors, consultants and volunteers - must have enough records management training to enable them to apply PROV’s standards. However, neither agency provides or has access to education and training that is adequate for the needs of those who deal with public records.

Both agencies are responsible for large numbers of highly sensitive records that are not all subject to adequate controls. The key control weaknesses we identified in the records management programs of each agency were largely similar:

- insufficient authority given to, or applied by, the central records management unit

- inadequate training for staff, contractors and consultants on their records management responsibilities

- little or no assurance by agencies that where third-party providers are being used, they are lawfully managing records of the services they are delivering on the government’s behalf

- compliance monitoring is absent or insufficient and reporting is not coordinated through the records management unit to the secretaries, limiting their visibility of weaknesses and hindering their ability to make informed improvement decisions

- noncompliance with the Capture specification, which requires agencies to have records that are authentic, reliable and usable, and have integrity—these requirements provide assurance that a record can be trusted.

DHHS & TRIM

“Some DHHS staff use TRIM, an electronic document and records management system, for managing some records. DHHS has approximately seven million documents in TRIM. Outside of TRIM, DHHS has approximately 100 million electronic documents across its network of drives and shadow systems (records repositories that are additional to the organisation’s records management system). This number does not include the documents in DHHS’s email systems.

“DHHS was unable to determine how many electronic documents were stored in staff email inboxes, and could only determine the number of emails sent and received across the agency over the last year. Of the combined total of 39.3 million emails, they were unable to determine how many had included records.

“A core reason for so many documents not being captured within DHHS’s endorsed records management system, when appropriate, may be because the system has only been deployed to 2,130 staff (20 per cent of the workforce).

“DHHS’s position descriptions and records management policy make it very clear that all staff are responsible for ensuring their own compliance with the Act - and DHHS’s records management unit is able to ensure the lawful management of records that staff capture in TRIM.

“However, where staff are choosing to manage their records outside of TRIM, in breach of the Capture specification, the records management unit does not have the authority to compel them to lawfully manage their records.

“DHHS’s central records management unit has worked hard to establish a system that supports effective records management. However, with so many documents sitting outside of TRIM, this work is not being used effectively throughout the agency. As a result, DHHS is not fully realising the potential benefits of its records management system or managing its risks

“We learned that an estimated 16 800 files are recorded in TRIM as ‘missing’. These include, but are not limited to, files for:

- hospitals, disability services and palliative care services

- human resources

- youth justice

- housing and homelessness

- protective services

- child protection.

“Of the 16 800 files marked as missing in TRIM, 622 are child protection files (0.2 per cent of the child protection files in DHHS’s corporate records system), with some marked as missing since 2004 and 2005.

Known Unknowns at DET

“DHHS operates in one of the more mature records management environments. Because of this, DHHS was able to provide us with a large amount of information on the state of its records management. In contrast, DET’s broad non-compliance with PROV’s standards means that the agency knows very little about its entire records holdings.

“Across the agency, more than 50 different locations are being used for records storage, but the records management unit has no control of them or access to them. There is also a large but unknown number of storage units, storerooms, filing cabinets and other storage repositories spread across the agency in undocumented locations— containing potentially many thousands of boxes of records. DET could not provide information on missing files, or files in transit, and is largely unaware of the extent of the risks related to its records management.

“Like DHHS, DET was also unable to determine the number of records held in email inboxes, or the number of sent or received emails that contained records. They could determine the number of sent and received emails over the last six-month period— approximately 196 million.

“Unlike DHHS, DET was only able to determine the number of files in one of its eight shared drive areas—approximately 3.8 million files. Because there is no assurance of the uniformity of the eight areas, any extrapolation of file numbers from this single area would only be speculative. As with DHHS, DET is unable to determine how many of those files are agency records.”

The report highlights previous inquiries in 1996 and 2008 which both found that “Victoria’s records management legislation was outdated and unfit for purpose.”

“PROV has achieved positive change since our 2008 audit, overcoming a past lack of support from DPC for initiatives to improve records management. In particular, PROV’s release of improved records management standards and agency tools has strengthened the public sector’s ability to effectively manage the government’s information.

“However, further reform is needed, as longstanding weaknesses in Victoria’s regulatory framework remain.”

In June 2016, the Victorian state government announced it will undertake a full review of the Public Records Act 1973. The Auditor-General’s report notes that a similar commitment made in 2008 only made it as far as the commissioning of an “options paper” (When this audit was completed in March 2017, the review had not begun.)

The full report is available HERE

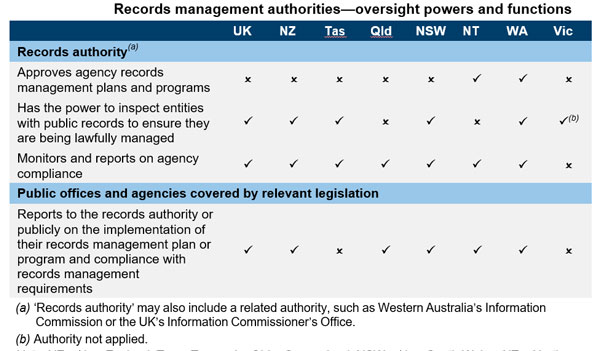

The Victorian Auditor General found that “Victoria’s oversight of public records management is significantly behind other jurisdictions, particularly those that have adopted the use of audits or assessments to ensure that agencies implement better-practice records management.” The current penalty for destroying records without an authority in Victoria is five penalty units (approximately $A777.30). In comparison, maximum penalties for records management offences in other jurisdictions range from fines of $A3,600 at the Commonwealth level, to $A30,800 in NT. Offences in NT and SA can also incur prison terms of up to one year and two years respectively.