What the “The Good Place” teaches us about effective business automation

The Good Place” is an NBC TV series starring Kirsten Bell that finished up this year. It is an unusual TV series, not just because it concluded whilst its popularity was on the rise, but also because its core themes were philosophical.

If you haven’t seen the show now is a good time to warn you that this article contains philosophical spoilers.

In The Good Place, the main characters discover that no one has gotten into heaven in hundreds of years. The reason no one is getting into heaven is because it is much more difficult to be a good person today than it was in a pre-industrialised, pre-globalised economy. Before the industrial revolution, the socks you wore were free of negative consequences. The wool came from sheep on your neighbours farm and they were knitted by your grandmother. Today, the socks you wear may have been manufactured by child labour and shipping the socks to you has contributed to climate change. The explosion of complexity and interrelationships in the world has made it so no one can be truly good these days and, therefore, according to the Good Place, no one is getting into heaven.

A similar dynamic is at play in business automation. Despite advances in technology, it is increasingly difficult to effectively automate your business. In the past, an insurance company may have dealt with a few dozen brokers and it was comparatively easy to build effective processes with them. Today, that same insurance company may deal with thousands of brokers each with different claims and policy writing processes.

Surprisingly, the solution to effectively automating your business in an increasingly complex environment is the same solution Kirsten Bell and her co-stars used to get good people flowing into heaven.

In our book, Machine Learning for Business, we use the Solow Paradox as the jumping-off point into the application of machine learning in business automation. Understanding the Solow Paradox is the key to answering the question: “Why, despite advances in technology, is it so hard to deliver meaningful change in a business?”

The Solow paradox is named after Robert Solow, an MIT economist in the 1980s.

The mid-1980s saw the spread of IT across companies of all sizes. Before then, if you had an IT system, you were a big company with lots of resources. But the rise of the personal computer led to broad adoption of software solutions in smaller companies.

In 1987, Robert Solow, reviewing a book announcing the age of Programmable Automation, said, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the [labour] productivity statistics.”

What he means by this is that, by 1987, computing power and the use of computers had rapidly increased but productivity hadn’t grown very much. And that trend has continued. Today, computer chips are 20 million times more powerful than they were in 1970 but each hour we work we only produce twice as much value as we did in 1970.

To an economist, labour productivity is the total dollar value of goods and services produced divided by the number of hours of labour it takes to create that value. So, your personal productivity is the amount of value you generate in a year divided by the number of hours you work. A country’s productivity is the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) divided by the number of hours worked by every worker in the country.

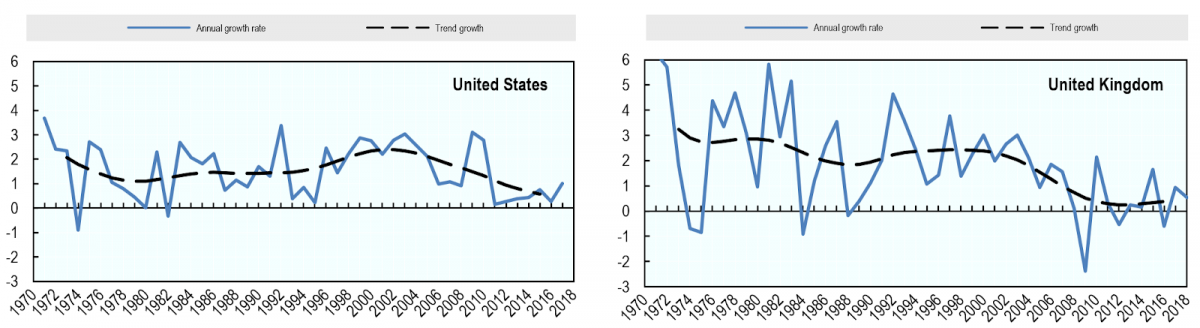

Since 1987 when Robert Solow described the Solow Paradox, productivity growth has slowed rather than sped up. The charts below show the annual productivity growth (the percentage annual increase in productivity compared to the year before). When Robert Solow made his productivity quip in 1987, annual productivity growth in the US and UK was sitting on either side of 2%. Now, both are below 1%.

OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2019

You can see this same trend at the micro level as well as the macro level. For example, forty years ago, commute speeds in Los Angeles were 25% faster than they are today. The increase in complexity (number of vehicles) has outpaced improvements in car technology and road infrastructure.

The paradox part of the Solow paradox is that no one really understands why productivity is not increasing. My personal theory is that is the same reason that, in the TV show, The Good Place, no one is getting into heaven anymore. In The Good Place (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Good_Place), the world’s increasing complexity has made it so no one can be truly good anymore.

The Solow Paradox is partly explained by this same phenomenon. As the world gets more complex, it becomes harder to deliver value. Complexity is like a headwind slowing us down. A hundred years ago Henry Ford’s team took 2.5 hours to manufacture each Model T. In 2016, Tesla was taking 3-5 days to manufacture each Model S. Each year the winds of complexity blow harder. Just to stay still, you need to make your processes more streamlined and better able to cut through the headwinds.

So how does this relate to maximising the productivity of your company?

When you look at improving productivity in your company, you face the same complexity headwinds faced by our economy as a whole. The interconnectedness of everything means it is really hard to deliver productivity improvements, and getting harder. So how do you do it?

Here are the real spoilers so, if you are going to watch the show and you don’t want to know how it ends, stop reading now. Come back after you’ve binged the series. :)

The solution successfully adopted by the characters in The Good Place was to provide a feedback loop and allow people to go through life again - retaining some of the knowledge they learned in their previous iterations. This allowed people to adapt to the complexity, live good lives despite it and eventually reach heaven.

Similarly, in business automation, the complexity of most business environments is such that you aren’t going to get it right the first time. But you’ll learn some things that will help you get it more right the next time. So, when you’re designing your projects, build in an iterative component that lets you improve over time and you'll eventually make it into automation heaven.

Doug Hudgeon is the CEO of EQ8R Managed Functions (https://eq8r.com). Managed Functions are automated business processes that enterprises deploy to the cloud. He is the co-author of Machine Learning for Business, a new book from Manning Publications. When not working, presenting or writing he can be found exploring waterholes along the Australian coast with his wife and two daughters.