Why information governance is the new black

A natural tension between freedom and control for public sector information assets can easily create obstacles to transformation and a shift to digital processes. Information governance empowers you to get the balance right.

Consider this: “On the one hand, information wants to be expensive because it’s so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life.

“On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of getting it out is lower and lower all the time. So, you have these two things fighting against each other.”

In an era when tech trends seem to come and go like teenage fashion, this paradox was first put forward by seminal technology pioneer, futurist and environmentalist Stewart Brand, at the first “Hackers” conference in 1984 in Marin County, California.

The statement hails from an era when a DIY computing counter culture spawned such giants of innovation as Apple and Microsoft, along with others long since forgotten. ‘Information wants to be free’ became a catch cry for cypherpunks and hacktivists.

That assertion might sound like the perfect truism for working in modern government today as the drive for digital transformation gathers pace.

But it’s really Brand’s first observation – the potential for the right information in the right place to change lives – that’s even more relevant today than it was then, and here’s why:

Since the dawn of the internet age we have become an information society. Our lives at work and at home, in business and social activities, revolve around accessing and exchanging information.

The public sector is still under pressure to be more open, more transparent and to release more data. Agencies are also regularly the subject of public and media criticism stemming from concerns about privacy, cybersecurity and excessive or intrusive collection of data.

Like Brand’s paradox, there’s an inherent tension between freedom of, and control over, information which can easily create obstacles for public sector transformation and a shift to digital processes.

How then to address both parts of the puzzle and get the balance right?

Information governance provides an authorising and accountability framework for creating, valuing, using and managing information assets. It takes account of business needs, legal and regulatory obligations.

It establishes roles, responsibilities and reporting requirements, along with principles you can build into operational processes and IT systems to enforce controls or streamline decision making.

Information governance is not new but has experienced a sudden spike in popularity. Once the preserve of records managers or compliance officers, information governance is now recognised by all levels of the organisation, from ministers through to frontline staff, as a key to safety and agility.

Not only that, it is acknowledged as a foundation for the entire transformational journey to a digital government.

In the digital age, everyone knows how great it feels to have the right information in the right place when we need it most – customers and service providers alike.

Good governance enables agencies to be collaborative, mobile and transparent, while ensuring information accuracy, reliability and security are never compromised.

If you don’t see up-front acknowledgement and detail on information governance on your transformation roadmap, it may be time to start asking questions.

Information needs to flow to add value

Ministers and senior executives now recognise that all business – including government business – today runs on data and digital information. It flows through every process, underpins policy, powers transactions and has the potential to drive whole economies.

Information can, and must, move between different people and organisations, for a variety of uses or actions and to support services and decisions.

Organisations that ‘go digital’ increase the speed and efficiency of their work processes by letting information flow. They frequently report further benefits including business insights based on real time data and a growing culture of innovation.

But it’s important to remember that just ‘going digital’ without solid underlying governance structures can produce unintended consequences that detract rather than add value.

If the value or integrity information diminishes, it can quickly erode public trust, or expose key stakeholders to serious liabilities – if it is the wrong information, or ends up in the wrong place.

Add mandatory disclosure obligations for data, privacy or information security related incidents and it’s not difficult to identify where the pain points can occur.

Allowing multiple parties within the organisation to view, reuse or contribute to an information asset can increase the value of that asset. This reduces the relative cost of producing the right information and offers broader public benefits when limited resources can be put to optimal use.

The “info-flow” challenge

Most agencies have developed robust information governance frameworks to manage their complex mix of risks and balance public interests. That’s a good thing.

Such frameworks take significant investment of time and expertise and are intended to streamline decision making and appropriately release or protect information with a minimum of bureaucracy.

The challenge for digital process transformation arises because information governance is usually stuck in a box. It’s often attached to a single system or silo where the information is stored.

While information is stored in that box, it’s managed and controlled. Once out of the box, information may move through ungoverned channels where it is more difficult to track or protect and this legitimately makes people nervous.

Nevertheless, information still needs to flow to be useful.

People respond to this tension in different ways. Common behaviours include:

- Holding onto manual processes, which feel safer because they’re slower, but create an efficiency drag.

- Or moving information into and through ungoverned digital channels, based on a case-by-case assessment that benefits will outweigh the possible risks.

Neither scenario is optimal.

Process governance for secure ‘info-flow by design”

By linking existing information governance to process automation you can set governance free to follow the information where it needs to go. Information doesn’t have to live in one place. It can safely travel between different systems.

We call this process governance.

Process governance means people can continue to work in familiar applications from any location. Staff are empowered to share and release non-sensitive information, safe in the knowledge that protections for privacy and security are built into the process by design.

Automation brings information to the right place, where and when it is needed.

Process governance applies information governance in the background, every step of the way, and controls risks by ensuring it’s the right information and access to it is managed according to established rules.

Importantly, process governance also allows transformation to be tackled incrementally – or ‘chunked down’.

Where knowledge workers gather

A steady supply of reliable data and information is the currency of knowledge workers, executive or operational, in government today.

Their success also depends on opportunities to communicate and collaborate with peers and stakeholders, who can review or contribute to their work.

Digital government relies on collaboration and information exchange across teams, between agencies and jurisdictions, with service providers and customers. The synthesis of diverse perspectives supports innovation, decision making and actively manages risk.

It drives better service design, policy development and strategic planning.

Of course, agencies are the trusted custodians of personal and other sensitive information relating to health, law enforcement, environmental, cultural or commercial matters. They have a responsibility and a legal obligation to protect people’s rights and ensure accountability.

Former Australian Public Service chief Peter Shergold AC stresses the fundamental importance of good records and collaboration across sectors as a critical success factor in government policy initiatives.

Shergold also highlights the real risks of ‘solutioneering’ before properly scoping the problem, and then trying to re-engineer crucial governance requirements.

The collaboration challenge

An urgent and growing need exists for the public sector to partner with industry and non-government organisations to deliver efficient, targeted services and improve public outcomes.

In a report commissioned by the NSW Public Service Commission, Nous Group identified the “size and complexity of public sector structures [and the] fragmentation of knowledge across these structures” as a core driver of cross sector collaboration to allow different experts to work together to solve multi-faceted problems.

Critically, the report identified governance as a key enabler of successful collaboration.

The collaboration challenge arises because information governance usually stretches only as far as the boundaries of the organisation. The use of unsanctioned digital channels or “shadow IT” for collaboration and sharing information with external parties can erode information security and auditability, impacting value and integrity. It exposes agencies to a variety of risks including unauthorised disclosure of information, duplication and version control issues, and (ironically) the creation of information silos.

So here, again, we have this tension between the concepts of freedom and control. On the one hand, productivity and the value of information is potentially increased by collaboration. On the other hand, security, privacy and the quality of the information may be compromised by collaboration.

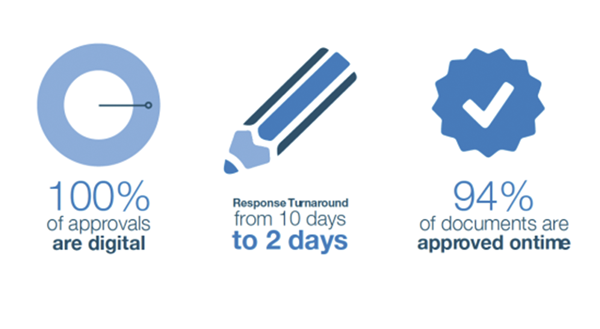

Transformation benefits are real. These metrics come from a NSW government central agency.

Collaboration governance for secure sharing

By linking existing information governance to shared workspaces, agencies can extend their governance policies into the places where knowledge workers gather. Information can be safely shared outside the team and beyond the boundaries of the organisation.

We call this collaboration governance.

Collaboration governance means people can work effectively together and partner in a variety of ways with access to the information resources they need, whilst maintaining the integrity of the information along with the rights and responsibilities of all stakeholders.

Shared workspaces enable knowledge workers to share ideas and expertise, bringing information to the right people, where and when it is needed.

Collaboration governance applies information governance in the background. It controls risks by ensuring it’s the right information and that access to it is managed according to established rules.

Embracing ‘the new black’ for digital transformation

Information wants to be free – free to flow to the people that need it most and the places where it is most useful.

Information also has value to those who produce, procure or are parties identified in the content. Its integrity and security are equally as important as its availability.

Digital era government provides the opportunity to:

- transform processes and let information flow, to support better services and faster decisions

- address the collaboration challenge and securely share information with other parties to solve complex policy problems.

The right information in the right place does change lives for the better, that’s why today information governance is ‘the new black’. Digital fads may come and go but good information governance will endure well into government’s digital transformation and beyond.

Sonya Sherman is a data and information specialist for Objective Corporation supporting innovation, collaboration and digital transformation in government business. She has held senior public policy and advisory roles in Australia, UK and the Caribbean. Sonya is a strong advocate for digital transformation in the public sector, maximising the use of data and information for better policy outcomes and greater public value.

Sonya Sherman is a data and information specialist for Objective Corporation supporting innovation, collaboration and digital transformation in government business. She has held senior public policy and advisory roles in Australia, UK and the Caribbean. Sonya is a strong advocate for digital transformation in the public sector, maximising the use of data and information for better policy outcomes and greater public value.