The Inevitability of Automation

Automated records and information management has been on the horizon for over 10 years, but Australian government and regulated entities are only now making their first forays into the brave new world of automated control systems.

The drive to automate comes partly from Federal government (the Department of Finance recommended a move to automation in 2015), but mostly from the impracticality of continuing to register, sentence and dispose of records using people-power. The problems experienced by government agencies in trying to grapple with their records using traditional systems are compounding and require a change in approach.

The National Archives of Australia (NAA) does make it clear that entities need to manage all their evidence of business (which includes almost all content, in all systems, and of all formats). It has been running the Check-Up process in various incarnations since 2014, and is still only seeing 12% of agencies doing any disposition of digital records.

The NAA is working on a post-2020 strategy now, and a new plan on driving agency compliance can be expected within the next 12 months. NAA will continue engaging with the C-Suite of government to drive home the importance of controlling our digital records properly.

But it’s not just National Archives putting pressure on agencies to manage their records effectively. Many other pressure points exist on information and records

managers, and the pressure is going to continue to grow, in some cases exponentially.

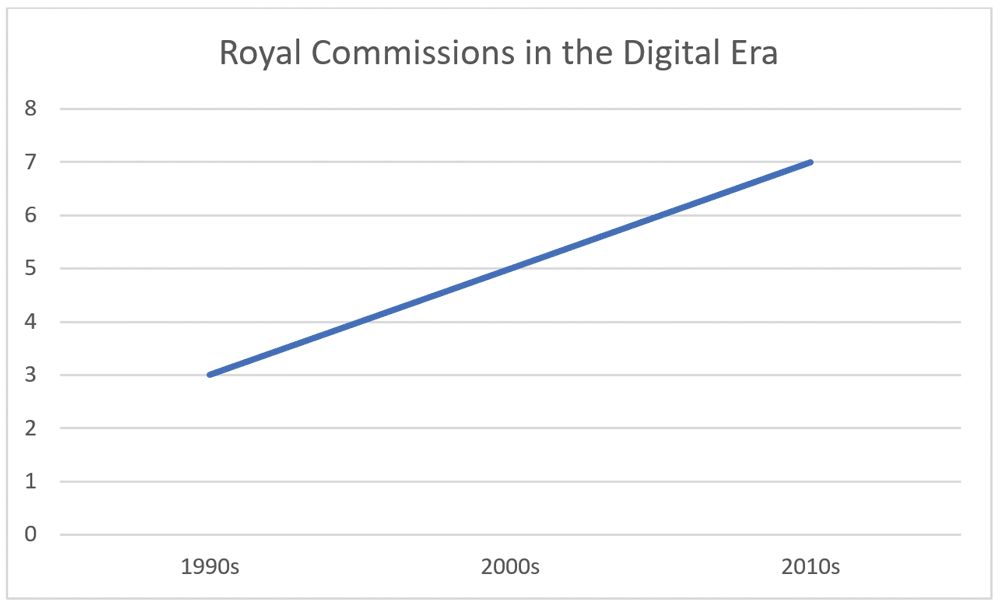

The amount of regulation we are subject to is increasing, as is the scope of information it spans. One other source of stringent, but unpredictable, record requirements is Royal Commissions. These often relate to topics that have not been explicitly considered in Records Authorities or in legislation.

When a Royal Commission is announced, historical and current records about a certain subject are suddenly needed, and must be dredged up – and then protected from any deletion or modification for the duration of the inquiry. In the current decade, there have already been seven Royal Commissions at the federal level, with more possible by 2020. The numbers are small, but there has been an uptick over the last 30 years.

The first 50 years of Royal Commissions focused mainly on industry, government and financial inquiries, with some military and sociocultural topics addressed early on. Over the next 50 years, while government and industry remained hot topics, crime, disaster, military and national security topics also became more important.

But the last decade has seen a significant focus on sociocultural issues (i.e. child sexual abuse, youth detention and aged care). In fact, over 50% of all sociocultural Royal Commissions for the last 120 years have been established in the last 5 years.

Sociocultural inquiries affect more agencies. Government has the mandate to establish, enact and enforce laws, and laws are intended to protect the welfare of citizens. Essentially, government overall is supposed to protect our sociocultural values.

While some departments may have a lot to do with industry, crime or national security, most are established to support sociocultural goals. As such, more ‘sociocultural’ Royal Commissions may mean more records discovery and control impact on more agencies – and agencies need to be prepared for this.

Disposal Freezes

In addition to Royal Commissions, there are other types of disposition holds enforced by the National Archives. There are 12 current freezes/retention notices include those relating to current and recent Royal Commissions, as well as AFFF fire suppressants, allegations of abuse in Defence, superannuation, atomic testing, the Vietnam War, and indigenous rights. Again, a range of topics from military to sociocultural – and hard to predict before they arose.

The fire suppressants freeze, for example, is for PFAS chemicals, which have not previously been considered hazardous. If agencies have ‘prioritised’ their record

governance to focus only on known hazardous chemicals, they may have not instituted any controls over PFAS-related records. In many cases, key records that could help determine key facts in the legal cases are ‘missing’. This means that now, when we have found out that these substances can be harmful, we are not in a position to see the full history of their use.

Of the 12 freezes and records retention notices currently in place, two date from the 80s, and one from the 90s. In the past 10 years since 2008, there has been an average of one new freeze or notice issued or extended every year.

If this trend continues, that implies a new category of records every year that must be found, no matter what system or format they are in, and some kind of control applied to ensure sure they are not deleted, destroyed or modified without authorisation. If most of these records are in non-EDRMS systems with no records management control over them, it won’t be possible to meet this legal obligation to freeze them in whatever system they reside.

ANAO Audits

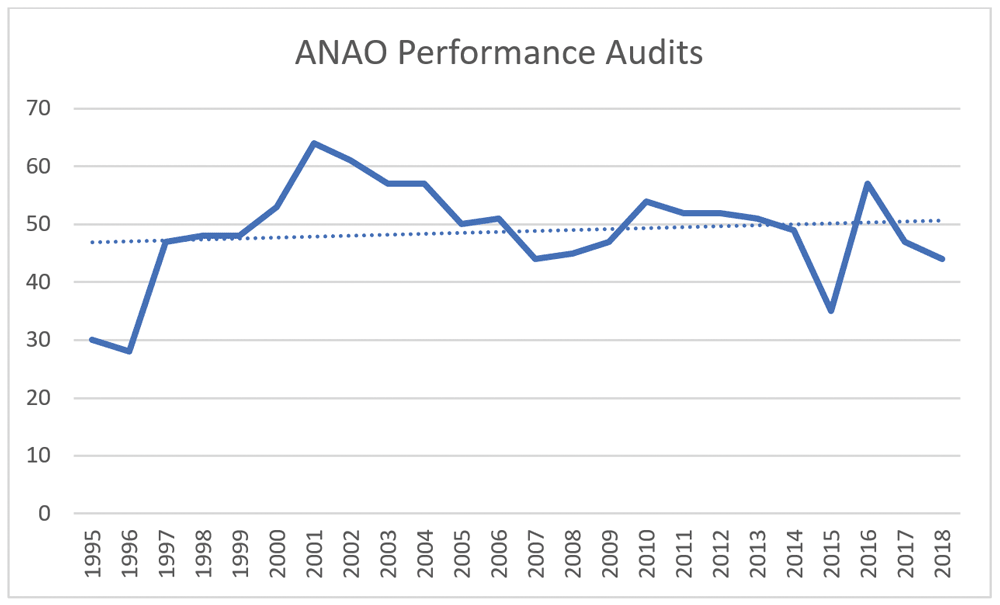

Separate to the NAA, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) can and frequently does require agencies to furnish all records related to a topic. There are approximately 50 audits a year, spanning all departments, and ANAO Performance Audits are trending overall slightly up.

ANAO audits already take on average 10 months, and place a large burden on records and information managers to help the auditors source and verify in-scope records, sometimes dating back many years. The ANAO is now taking a more data-enabled approach to its audits, which may mean more requirements to furnish data from structured systems and databases, not just documents and emails.

Freedom of Information requests

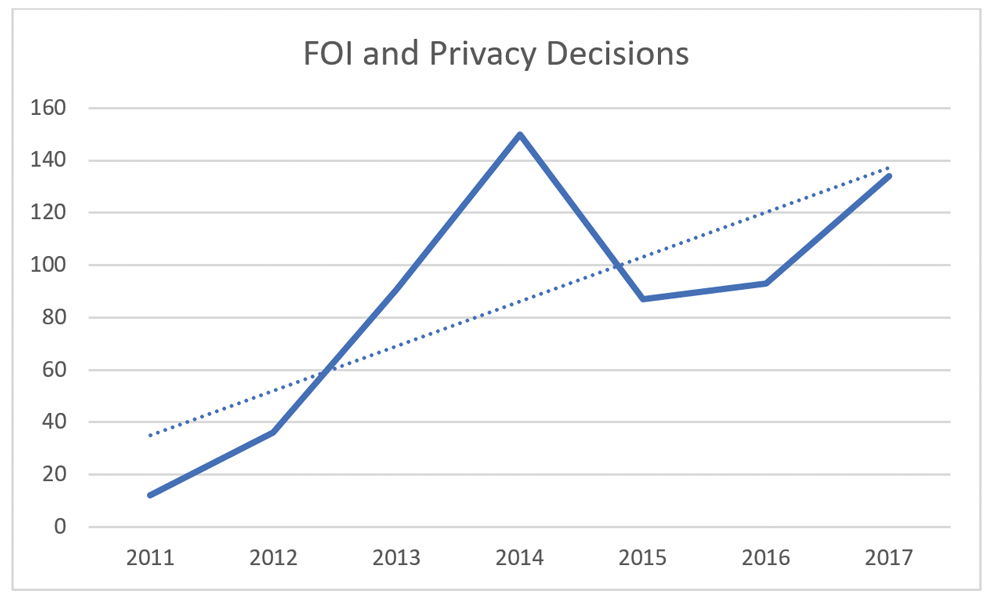

Another major demand placed on government records managers is the growing number of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests and Privacy discoveries. The cost of these discoveries is increasing at 300% ahead of inflation.

The chart below shows the number of complaint, review or other decisions made since 2011 by the Australian Information, Freedom of Information or Privacy Commissioners, under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 or the Privacy Act 1988.

These escalated cases incur extra cost to agencies, and we can see that the overall trend is definitely a steep upward one since reporting started in 2011.

So, disclosure requests, costs and review actions are increasing steadily, well outpacing inflation and population growth. All this means that government agencies need records kept in a very good state.

Not only do they need to be able to respond to FOI requests that do arise more quickly and much more

efficiently, but they also need to be able to demonstrate that they have actually taken reasonable steps to find in-scope records, to minimise the number that are escalated to the Commissioners.

And of course, record-keeping needs to be done well in the first place, so that there aren’t as many mistakes that can trigger FOI discoveries or privacy complaints.

Security and Privacy Breaches

In the above cases, agencies will be compelled to furnish their records to those requesting them. If they aren’t able to find key information, or if they provide extraneous,

outdated or incomplete information, the job of the investigators will be made more difficult, and the potential rebound on the agency could be significant.

For this reason, agencies have to expend a lot of effort in searching thoroughly for relevant records, and then in reviewing and sanitising those records (including redacting sensitive information) so that only the information in scope of the request is provided.

But for another group that want access to agency data, there is no polite request process. Agencies do not have a chance to sanitise what they take, or even know it has been taken. Threat actors, including foreign intelligence services, cybercriminals, and organised crime groups can come into possession of agency records by attacking networks, or by exploiting malicious or careless insiders. They can also change records, or destroy information, often without detection.

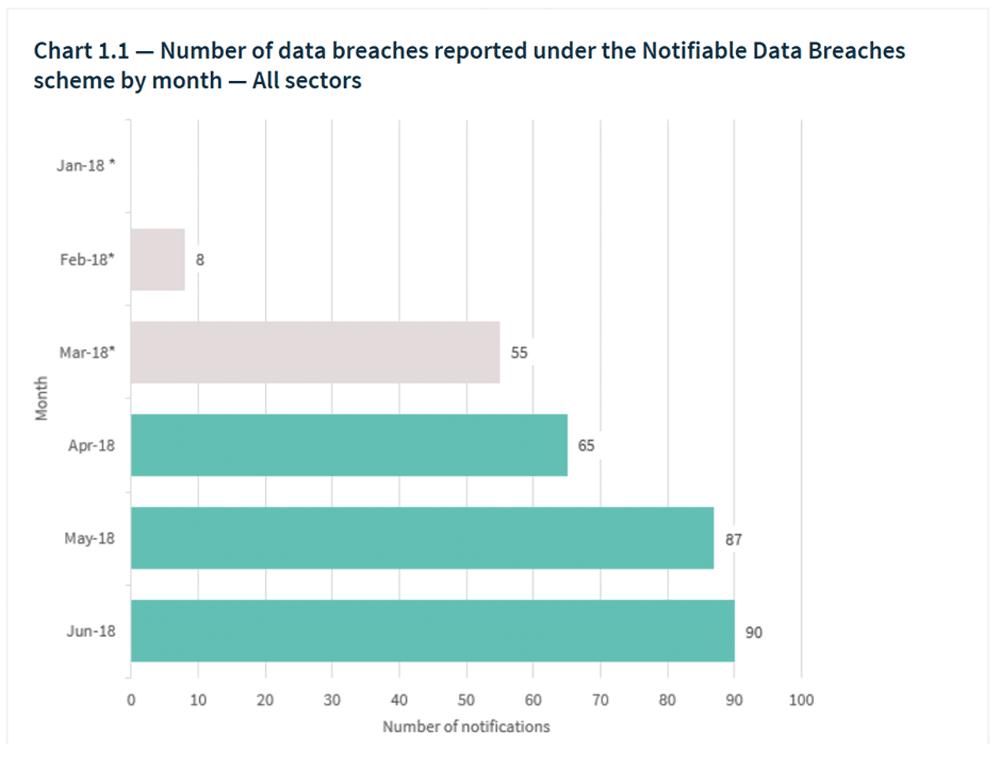

We looked already at the rising costs of data breaches globally, but we can look closer to home this year thanks to the Office of the Information Commissioner’s Notifiable Data Breaches Scheme. Since the scheme commenced, reported breaches have steadily increased every month.

Malicious attacks accounted for 59% of the reported breaches.

Attacks and other breaches are increasing at a steady rate. The more data we have, the more data we have at risk of being exposed in one of these breaches. There are only three ways to reduce the risk of a confidentiality, integrity or accessibility breach of sensitive records.

Firstly, by not capturing them in the first place. Secondly, where they are required to be captured, by securing them effectively. And finally, where they are no longer required to be retained, by securely and permanently destroying them.

Agencies who do not have full insight into, and control of, their business systems, may not realise they are storing high-risk information that they don’t need, or that they don’t need any more.

If we can’t find where all our potentially sensitive records are, especially in legacy systems, we can’t protect them properly. A failure to records-manage business systems, which hold most of our important data, is a failure to secure our information.

The last word

The uptick in Royal Commissions, disposition freezes, the increase in legal discoveries, more and more FOI and privacy discoveries, the increased ANAO focus on big data, and the increase in deliberate and accidental breaches of information are all good reasons to take stock of your holdings, understand exactly what you have, and dispose of what you absolutely don’t need. Especially because all of these factors have a multiplier – more data.

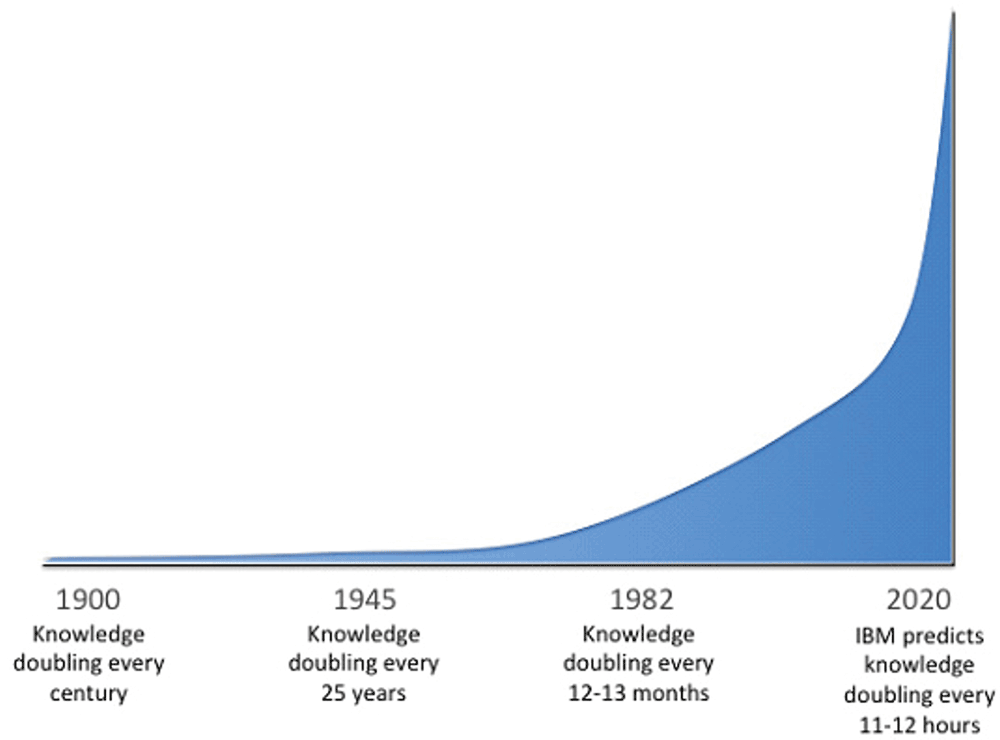

The population is growing. And the public sector is growing overall. More staff are producing more records, about more people. And that looks a little bit like this:

This is the Buckminster Fuller Knowledge Doubling Curve (with later addition by IBM). It predicts that by 2020, global knowledge will double twice a day. This represents an exponential increase.

More systems (including internet-of-things and AI systems) exist; they generate more data than traditional human-driven systems; data sets (and data users) are interconnected; and we collaborate and share information more than we used to. Government has embraced collaboration, and is starting to embrace big-data and AI. The information landscape is changing, and it’s getting much, much bigger. As we have an exponential increase in information, we have a commensurate increase in risk and cost. And because information grows and changes so rapidly, it becomes obsolete much faster.

We don’t buy leather bound encyclopaedias anymore, because they become outmoded almost immediately as new discoveries are made. In the same way, documents we wrote and relied upon up to a decade ago become less and less useful over time, as so much changes in the interim. Information comes at us faster and faster, but it has a much shorter useful lifespan.

This is particularly tricky for government, as we may still have legal obligations to keep records for years or decades, even if their ‘usefulness’ was only weeks or months.

It is becoming increasingly obvious that automation is the only answer to getting a good handle on this rapid influx of data.

Rachael Greaves is Chief Information Officer at Castlepoint Systems. For further information visit https://www.castlepoint.systems or call +61 488 114 767.